SPERMAGEDDON OR SCIENCE? INVESTIGATING RFK JR.’S ALARMING FERTILITY WARNINGS

Introduction: Fertility Fears and RFK Jr.’s Claims

Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. “RFK” Kennedy Jr. has repeatedly sounded alarms about an alleged crisis in male fertility. In interviews and congressional testimony, he has claimed that teenage boys today have half the sperm count of older men and dramatically lower testosterone levels – even asserting a “teenager today has less testosterone than a 68-year-old man”. These dire pronouncements are used to warn of an “existential” threat to human reproduction. Such statements tap into growing public anxieties that modern life is sapping male virility. On social media and wellness forums, terms like “fertility crisis” and “sperm count apocalypse” circulate widely, and a 2022 study found “semen retention” was the most-viewed men’s health topic on TikTok and Instagram.

But how accurate are RFK Jr.’s sensational statistics? Do today’s young men really have only half the sperm count of older generations? And if sperm counts are declining, is humanity truly on the brink of an infertility-driven collapse? This blog will examine the scientific evidence behind these claims. We will explore why RFK Jr. might be emphasizing this data, examine decades of research on sperm counts and male fertility, and distinguish facts from exaggerations.

Why Is RFK Jr. Talking About Sperm Counts?

RFK Jr. has a long history as an environmental health activist, often drawing attention to chemical exposures and public health issues he feels are ignored by mainstream authorities. Now, as HHS Secretary, he appears keen to spotlight male fertility as a barometer of population health. “We have fertility rates that are just spiraling… Sperm counts are down 50%,” he declared on Fox News. According to an HHS spokesperson, The implication is that pollutants, lifestyle changes, or other modern factors are stealthily undermining men’s reproductive capacity – and that Kennedy aims to force a conversation about it.

There may also be a political and cultural subtext. Concerns about falling sperm counts resonate with a broader “men’s health” or even “masculinity” narrative in certain circles. Influential figures like Elon Musk have warned that declining birth rates could spell societal collapse. By highlighting sperm count data, RFK Jr. taps into these currents of concern. He positions himself as a truth-teller about a crisis that, in his view, the government and medical establishment have failed to adequately address. Given his background, Kennedy likely believes environmental chemicals (endocrine disruptors), poor diet, and lifestyle factors are at the root of the problem – and he sees raising awareness as a first step toward remedies.

However, even if well-intentioned, RFK Jr.’s specific claims are scientifically shaky. For one, it is biologically implausible that teen boys have lower testosterone than 68-year-olds – in fact, testosterone naturally declines with age, so a healthy 17-year-old should have much higher levels than a man in his late 60s. And while Kennedy says “sperm counts are down 50%,” he conflates age-related differences with generational trends. Older men do tend to have lower sperm counts than young men (simply due to aging effects on testicular function), so comparing a teenager to a 68-year-old is misleading. More importantly, data on sperm counts specifically in teenagers is extremely sparse. Semen analysis is rarely done on minors, so we lack robust statistics on what the “normal” sperm count is for today’s adolescents versus those of decades past. In short, the premise that a teen boy’s sperm count is half that of a senior citizen is not supported by any published research – it appears to be a misunderstanding or misrepresentation of scientific studies, which we will discuss in detail.

Before we dive into the evidence (or lack thereof) behind these alarming proclamations, let’s clarify some basics about sperm counts and fertility. This will help us interpret what a “50% decline” truly means and whether it signals a fertility catastrophe or a more nuanced public health trend.

Sperm Count 101: What It Is and Why It Matters

Sperm count refers to the number of sperm present in a man’s semen, typically measured as sperm concentration (the number of sperm per milliliter) and/or total sperm count (the total number of sperm in an ejaculate). A related measure is sperm motility (the percentage of sperm that are moving) and morphology (the percentage of sperm with normal shape). These parameters are assessed via a semen analysis – a routine lab test for male fertility evaluation. In general, higher sperm counts (and better motility/morphology) are associated with higher fertility potential, though the relationship is not absolute. Many men with “suboptimal” counts can still father children, and conversely, some men with high counts may experience infertility due to other factors.

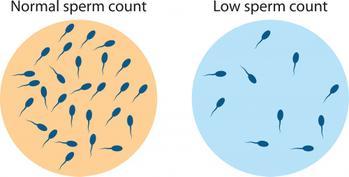

Medical professionals consider a sperm concentration of 15 million per milliliter as the lower reference limit for “normal” (per WHO guidelines), and motility above 40% and normal morphology above 4% are typical thresholds. Counts below 15 million/ml are termed oligospermia (low sperm count), while complete absence of sperm is azoospermia. It’s important to note these cut-offs are somewhat arbitrary and fertility can decline gradually as counts drop. As Dr. Jorge Chavarro of Harvard explains, “You have to get to pretty low sperm concentration levels before you start seeing an impact on a couple’s ability to become pregnant”. Often, fertility is only significantly impaired once counts fall well below 10 million/ml or motility is very poor.

For context, typical fertile young men often have sperm concentrations between 40–100 million/ml, with total counts per ejaculate in the hundreds of millions. If an average or “median” count in a population drops from, say, 100 million to 50 million, that sounds dramatic (50% decline), but 50 million per ml is still above the threshold where most men would be considered infertile. Thus, when we discuss reported declines in average sperm counts, we must distinguish between a potential public health indicator and an actual fertility crisis. A decline in population average could warrant concern – possibly pointing to environmental or lifestyle issues – without necessarily meaning that large numbers of men are incapable of reproduction. Many researchers emphasize that even after reported drops, median sperm counts are still within a range compatible with normal fertility for most men.

It’s also crucial to know that sperm counts can fluctuate even within the same individual, depending on various factors. Frequency of ejaculation, for example, has a strong effect – abstaining for several days will generally increase sperm count in the next sample (up to a point), whereas daily ejaculation can temporarily lower counts. Seasonal variations have been observed (with slightly higher counts in winter than summer in some studies). Fevers or illnesses can suppress sperm production for a couple of months (spermatogenesis takes ~74 days, so a bad flu or heat exposure can lead to a dip in count weeks later). Even lab-to-lab differences in counting technique can introduce variability. All these factors make it challenging to measure “trends” in sperm counts over time – distinguishing true declines from noise or artifact requires careful study design.

With this background in mind, let’s examine the research that RFK Jr. and others cite when claiming sperm counts have plummeted.

The Decades-Long Debate on Declining Sperm Counts

Concern about sperm counts declining is not entirely new – it has been a topic of scientific debate for over 30 years. The issue burst onto the scene in the early 1990s with a headline-grabbing study, and since then, conflicting findings have left the matter unresolved. Here is a chronological overview:

- 1992: The Bombshell Meta-Analysis: A team of Danish researchers led by Elisabeth Carlsen published a review in the BMJ that sent shockwaves through the scientific community. They compiled 61 studies from 1938 to 1991, encompassing ~15,000 men, and reported a precipitous drop in average sperm concentration – from 113 million per ml in 1940 to 66 million per ml in 1990. That’s roughly a 50% decline over 50 years. They also noted a decrease in semen volume (from 3.4 mL to 2.75 mL). Their stark conclusion: “There has been a genuine decline in semen quality over the past 50 years”, possibly signaling a general reduction in male fertility. The authors even speculated that this decline was biologically significant, coinciding with rising rates of testicular cancer and genital birth defects, and suggested environmental factors (like hormone-disrupting chemicals) as a cause.

This study immediately drew massive attention – it has been cited thousands of times – and alarmed headlines followed (“Every man is half the man his grandfather was,” as one scientist dramatically testified to Congress in 1993). RFK Jr.’s talking point that “sperm counts are down 50%” traces directly back to this 1992 analysis. Indeed, Kennedy often references that figure in interviews, using it to imply modern men have only half the reproductive capacity of men mid-20th century.

- Criticisms of the 1992 Study: Not all experts were convinced. Throughout the 1990s, numerous papers challenged Carlsen et al.’s findings on methodological grounds. For example, it was pointed out that the data from the 1930s–1940s were very limited (few studies, small sample sizes), so the starting baseline might not be reliable. The included studies came from many different countries and laboratories that likely used different sperm counting methods, raising comparability issues. There was concern about selection bias – many early studies used men of “proven fertility” (new fathers or sperm donors), whereas later studies increasingly included men from infertility clinics or general population men not selected by fertility status. Such heterogeneity could create an artificial trend.

Additionally, statisticians noted that Carlsen’s simple linear regression might not be the best fit for the data. When other models were applied, the results changed. A 1995 re-analysis by Olsen et al. found that only a straight-line model produced a continuous decline – a spline (piecewise) model suggested a sharp drop in the 1960s followed by an increase in later decades, while a stepwise model showed no significant change over time. In other words, depending on how one models the data, the conclusion could flip from decline to flat trend. This highlighted how sensitive the 1992 result was to analytical choices.

Some large single-center studies also contradicted the decline hypothesis. Notably, an analysis of 1,283 men who banked sperm in the U.S. between 1970 and 1994 found no drop in counts – in fact, a slight increase in mean concentration was observed over those 25 years. Dr. Harry Fisch of Columbia University, who led that study, became a prominent skeptic, often arguing that the perceived global decline was a myth caused by mixing incomparable data sets. Similarly, a 15,000-man study in New York from 1951 to 1977 showed no change in semen quality, and a Canadian analysis of 48,000 men from 1984 to 1996 across 11 clinics found no consistent trend. These findings suggested that when you hold methodology constant (same lab, same population criteria), sperm counts haven’t necessarily fallen at all.

- 2000s: Mixed Evidence and “No Decline” Predominance: Through the late 1990s and 2000s, the literature on sperm count trends grew, with a mix of outcomes. In 2000, Shanna Swan (an American reproductive epidemiologist) published a re-analysis addressing some criticisms of the 1992 study. Using an expanded dataset up to 1996, Swan still found evidence of decline (especially in North America/Europe). However, other investigators published reports of stable or even increasing counts in certain regions. By 2010 or so, many experts believed the initial scare was overblown. Dr. Dolores J. Lamb, a renowned male infertility researcher, summarized that “for every paper that suggests a decline and raises alarm, there’s another that says numbers aren’t changing”. In fact, an extensive review reported that between 1992 and 2013, 35 studies on semen trends were published: 8 studies (18,000 men) suggested a decline, but 21 studies (112,000 men) showed no change or even an increase in semen quality. The remaining studies had ambiguous or conflicting results, meaning the majority did not support a clear downward trend. “The preponderance of the data suggests that there was no decline,” said Dr. Lamb in an interview, reflecting the stance that emerged among many urology and andrology specialists in that era.

- 2017: The Debate Reignited (Swan’s Meta-Analysis): The pendulum swung yet again in 2017 when Dr. Shanna Swan (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai) and colleagues published a high-profile meta-analysis in Human Reproduction Update. This study aggregated 185 studies from 1973 to 2011 (covering 42,935 men), making it the most comprehensive analysis to date. The findings were striking: in Western countries (North America, Europe, Australia/New Zealand), sperm concentration declined by 52.4% and total sperm count by 59.3% over the 38-year period. The average concentration among Western men dropped from about 99 million/ml in 1973 to 47 million/ml by 2011. Meanwhile, in South America, Asia, and Africa, no significant decline was detected – though the authors cautioned fewer studies were available from those regions. This publication garnered enormous media attention (with headlines like “Sperm Counts Halved in 40 Years” and even a Guardian article ominously titled “Falling sperm counts ‘threaten human survival’”). It thrust the sperm count debate back into public consciousness and lent support to those, like RFK Jr., warning of a broad fertility problem.

Swan’s team took pains to address prior criticisms: they included only studies that used comparable counting methods and men without known infertility or exposures, and they performed multiple sensitivity analyses. Still, skeptics noted that methodological differences over decades can never be fully eliminated – for instance, subtle changes in laboratory equipment or quality control from the 1970s to 2010s could bias results. As Dr. Allan Pacey (a British andrologist) remarked, “Are sperm counts declining? Or did we just change our spectacles?” – suggesting that what looks like a decline might be due to counting techniques improving over time. Moreover, the inherent variability and lack of a standardized, global sperm surveillance system make this kind of meta-analysis extremely challenging. By necessity, it stitches together many small studies with different inclusion criteria. The authors themselves acknowledged that the “ideal study” – a consistent, decades-long, worldwide sperm monitoring program – doesn’t exist.

Nonetheless, the 2017 meta-analysis galvanized both scientific research and public concern. RFK Jr. and others have cited it as proof that male reproductive health is in freefall, sometimes extrapolating to apocalyptic conclusions. In her 2021 book Count Down, Shanna Swan warned that if the trajectory continues, the median sperm count could reach zero by 2045 (meaning essentially that half of men would produce no sperm). Such a scenario is speculative – extrapolating linear trends indefinitely is fraught with uncertainty – but the soundbite was widely reported and amplified doomsday narratives.

Fig.: Some research indicates that average sperm concentrations in Western men declined by over 50% from the 1970s to 2010s. However, this finding is contested, and global data outside Western countries have been limited. The downward trend, if real, might signal environmental or lifestyle factors affecting male reproductive health.

- 2022: New Global Analysis and Ongoing Controversy: In late 2022, Levine, Swan, and colleagues updated their meta-analysis to include studies through 2018 and more data from Latin America, Asia, and Africa. Published in early 2023, this analysis reported that the decline in sperm counts is a worldwide phenomenon – not just in the West – with an overall drop of 51.6% in mean sperm concentration from 1973 to 2018 across all continents. Intriguingly, they noted the decline appeared to be accelerating in the 21st century: after the year 2000, average sperm count was falling around 2.6% per year, more than double the ~1.2% per year rate seen from 1973–2000. If true, that is indeed worrying. The authors called for urgent research into causes and preventative action.

Yet, many experts remain unconvinced that a “sperm apocalypse” is upon us. In fact, a number of studies published around 2021–2022 countered the narrative. For instance, a systematic review of 21 studies of U.S. men from 2000 to 2017 found that while sperm concentration and count did decline modestly (about 1.4–1.6% per year) among men with fertility issues, there was no significant decline among the general male populationwhen adjusting for confounders. Another meta-analysis in 2023 focusing on fertile men (those who had proven their fertility by fathering children or donating to sperm banks) concluded that sperm concentrations have remained relatively stable among fertile American men over the last 50 years. For example, one study of men who banked sperm before vasectomy (i.e. presumably fertile men) from 1970–2016 showed no decline in sperm counts over time – if anything a slight uptick.

These discrepancies suggest that the detected trends can vary greatly depending on the population sampled. If you sample more infertile men or delay childbearing (meaning older fathers), you might see declining counts; but among consistently fertile younger men, maybe not. As Dr. Scott Lundy, a reproductive urologist, noted, his own analysis found a “subtle” decline in U.S. men’s sperm counts over decades, but one so small it likely has no impact on actual fertility for the average man. He concluded “there’s no cause for widespread panic for the typical male” – hardly the stuff of human extinction scenarios.

- 2021 Editorial – A Meeting of Minds? Interestingly, an editorial in Fertility and Sterility in late 2021 tried to bridge the divide. It was co-authored by an eclectic group: Dr. Niels Jørgensen (from Denmark, echoing Skakkebaek’s early warnings), Dr. Dolores Lamb (the skeptic), Dr. Shanna Swan and Dr. Hagai Levine (the meta-analysis authors), and others. This piece acknowledged the importance of the question “Are sperm counts declining?” and its scientific and social implications. It noted that some controversy is “genuine and scientific,” while some pushback might be driven by industries with vested interests (drawing a parallel to how tobacco and lead industries sowed doubt on harmful effects). The editorial recounts the history: Carlsen’s 1992 paper and its critiques, Swan’s updates, etc. Interestingly, at one point the authors state bluntly: “These conclusions are patently false. There are no high-quality data that support a decline in semen parameters over time. The debate exists because of subpar data and interpretations over the past century.” This refers to the overly broad claims that semen quality has halved – indicating the authors (including Swan!) agree that prior evidence was not ironclad.

The piece then balances that by noting their own 2017 analysis showed a decline and that a “much broader consensus” has formed that sperm counts are dropping, evidenced by few challenges published afterward. It highlights that the ideal data are lacking – no universal sperm registry – so we must rely on imperfect studies and be cautious. It calls for developing a multinational monitoring system for reproductive health indicators. In summary, this editorial illustrates that even experts on opposite sides of the debate can agree on one thing: the data are difficult to interpret, and extreme conclusions (either “the sky is falling” or “nothing to see here”) are likely over-simplifications. We need better data, but meanwhile, it’s prudent to investigate potential causes of any decline and not ignore what could be a significant public health trend.

Bottom line: RFK Jr.’s dire proclamations are rooted in some real scientific findings (notably the 2017 and 2022 meta-analyses showing ~50% sperm count declines). However, he cherry-picks the most alarming interpretation without acknowledging the serious questions and conflicting evidence in the field. Yes, multiple studies – especially large meta-analyses – suggest that average sperm counts today are much lower than 40-50 years ago. But numerous other studies, including those focusing on fertile men, have found little or no change. The data can be marshaled to support either viewpoint depending on selection and methods. What most experts do agree on is that if a decline exists, it’s not yet at a level that men in general are incapable of reproducing. Average counts, even if around 40-50 million/mL, are still well within fertile range for most. Moreover, fertility rates (how many children people have on average) involve many factors beyond sperm count – chiefly social and lifestyle choices, as we’ll discuss in the next section.

So, RFK Jr.’s framing of a looming extinction due to male infertility is not borne out by current evidence. It is a contentious issue, not a settled crisis, and framing it as an existential emergency may be overstating the case. That said, declining sperm counts (if real) could be a canary in the coal mine for male health problems, and understanding what might be driving such changes is indeed important. In the following sections, we’ll explore possible causes – including lifestyle and environmental factors – and also distinguish between fertility rates and fertility problems, which are related but distinct issues in this discussion.

Fertility Rates vs. Fertility Problems: Is There a “Crisis”?

One reason the notion of a sperm count crisis catches fire is that it aligns with news of declining birth rates and fertility rates in many countries. It’s true that fertility rates (births per woman) have fallen significantly in the U.S. and worldwide over the past few decades. For example, the U.S. total fertility rate hit a record low in 2023, around 1.6 children per woman (well below the “replacement level” of ~2.1). Globally, fertility dropped from 5.06 births per woman in 1964 to 2.4 in 2018, and today roughly half of countries have fertility rates below replacement. These trends have prompted concern about aging populations and economic impacts (hence Elon Musk’s tweets about “population collapse”).

However, it’s critical to distinguish voluntary demographic trends from biological infertility. The primary drivers of lower birth rates are social: couples choosing to have fewer children, people delaying marriage and childbearing into their 30s, wider use of contraception, more women in higher education and careers, economic uncertainties, etc.. In many developed nations, surveys show ideal family size has shrunk; having one or two kids (or none) is increasingly the norm by choice. So, declining fertility rates do not necessarily mean an epidemic of infertility (inability to conceive). They mostly reflect intentional behavior changes and societal progress.

Of course, if male fertility were truly plummeting due to low sperm counts, we’d expect to see a rise in couples unable to conceive even when they want to. Is there evidence of that? Some data suggest male-factor infertility is a significant component of infertility cases – roughly 40–50% of infertile couples have a male factor contributing(often alongside female factors). But there isn’t clear evidence that the proportion of men with infertility has dramatically increased in recent decades. In fact, assisted reproduction use (like IVF) has grown, but largely because of women delaying childbirth (female age is the biggest infertility risk) and greater awareness/treatment, not a sudden surge of sterile men in their 20s.

It is true that some indicators of male reproductive disorders have risen. For instance, testicular cancer incidence has roughly doubled in many Western countries since the mid-20th century (though it’s still relatively rare). Conditions like cryptorchidism (undescended testicles at birth) and hypospadias (a genital birth defect) have also shown increases in some data, which some link to fetal exposure to endocrine disruptors. These have been collectively termed “testicular dysgenesis syndrome” hypotheses. But connecting those trends directly to falling sperm counts remains speculative.

One fascinating statistic: Even men with very high sperm counts can experience infertility, and conversely some with low counts succeed in fatherhood. There is a lot more to fertility than just the raw count: sperm motility and morphology, as well as female partner factors, timing of intercourse, etc., all matter. As Dr. Stanton Honig of Yale notes, one common cause of male infertility is varicocele (enlarged varicose veins in the scrotum). Varicoceles are found in about 15% of all men, but in up to ~35% of men with infertility problems. Importantly, varicocele is a treatable and reversible cause of male infertility – surgical or interventional repair often improves sperm parameters and fertility outcomes. This underscores that many causes of male infertility are addressable. Low sperm count itself can sometimes be improved with interventions (if due to hormonal issues, varicocele repair, lifestyle changes) or bypassed via assisted reproductive technologies like intrauterine insemination (IUI) or in vitro fertilization (IVF) with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI).

So, is there a fertility crisis because of men’s sperm counts? Most experts say no – at least not yet. As Dr. Chavarro and others emphasize, you would need average counts to fall extremely low (near the infertility threshold) to dramatically impact natural pregnancy rates across the population. We are nowhere near that point on average. Even Swan’s projection of “zero sperm count by 2045” was likely a provocative extrapolation to raise awareness, not a literal prediction – biology often doesn’t follow linear straight lines to zero. If counts did continue dropping linearly (a big if), well before hitting zero, we’d expect a more modest increase in infertility rates which could be mitigated by medical interventions.

That said, the lack of a current doomsday doesn’t mean we should be complacent. Declines in sperm count, if real, could reflect environmental or health problems that merit intervention for many reasons. And even aside from counts, other metrics like testosterone levels and sexual/reproductive dysfunction in men might be flashing warning lights. Let’s examine those briefly:

- Testosterone Levels: RFK Jr.’s claim that teens have less testosterone than older men is inaccurate, but there is evidence that men’s testosterone levels have declined over the past few generations. A notable study in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (2007) found a substantial population-level drop in testosterone in American men from the 1980s to early 2000s, independent of age. They observed about a 1% per year decline in average T levels. For example, a 65-year-old in 2002 had about 15% lower testosterone than a 65-year-old in 1987. Similarly, a 30-year-old man in 2002 would have lower T than a 30-year-old two decades earlier. This finding has been replicated – factors like rising obesity and lower smoking rates (smoking can slightly increase testosterone) explained only part of it. Researchers suspect environmental exposures or other unknown factors might be contributing. So while an 18-year-old today still has way more T than a 70-year-old today, that 18-year-old might have somewhat lower T than an 18-year-old from a generation ago. This generational testosterone decline aligns with sperm count concerns and suggests a broad pattern of male hormonal changes. Lower testosterone can affect libido, energy, and muscle mass, but subtle shifts in population averages may not be noticeable to individuals. It’s a complex issue: lifestyle (exercise, diet, weight) strongly influences T, so disentangling intrinsic declines from behavioral changes is hard. Nonetheless, it’s an active area of research, as lowered testosterone could be a proxy for other health issues.

- Sexual Development and Other Male Health Issues: Swan’s book and others point to trends like earlier puberty in girls and possibly boys, more genital abnormalities in newborn males, and even changes in sexual behavior or preferences (some fringe theories link chemical exposure to things like decreased male libido or virility). Most of these claims are controversial or unproven. But one real concern is that if sperm count decline is part of a bigger picture, it might correlate with things like increased obesity (which itself lowers fertility and testosterone) or exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals. For example, a study noted that boys who go through puberty later (after age 15) had on average lower sperm counts as adults – suggesting developmental factors in adolescence can affect sperm production. However, trends in puberty timing are influenced by various factors (nutrition, etc.), so it’s hard to pin on environment alone.

- Male Fertility Treatment Trends: Fertility clinics have indeed seen more men seeking evaluation, but that’s partly due to better awareness that infertility is not just a “woman’s issue.” Up to half of infertility cases involve a male factor, and men are now routinely tested early in the process. Treatments for male infertility (like varicocele repair, medications for hormonal issues, surgical sperm retrieval for blockages, etc.) have advanced. So, even if average sperm counts dropped somewhat, medicine has more tools to help those affected have children. If worst came to worst and sperm counts broadly fell into a very low range, technologies like IVF/ICSI could be scaled up (albeit at great cost) to avert a “fertility collapse.” Of course, that’s not a scenario anyone wants; prevention is far preferable.

In summary, falling sperm counts do not equate to a societal infertility crisis at this time. Fertility rates are down mainly by choice, not because masses of men are incapable of reproduction. However, the trend could be a symptom of broader health issues worth addressing. As Dr. Levine said, “low sperm counts might also be an indicator of poorer health among men more generally”. Sperm count, testosterone, etc., could be like the “check engine light” on male health. It prompts the question: what’s driving these changes in male reproductive health parameters? That leads us to consider possible causes – particularly lifestyle and environmental factors that RFK Jr. and others often blame.

Potential Causes: Lifestyle, Obesity, and Environmental Chemicals

RFK Jr. has pinned the blame for purported falling sperm counts on two main culprits: rising obesity rates and exposure to environmental chemicals (notably endocrine-disrupting chemicals like certain pesticides or plastics). Let’s examine the evidence for each, as well as other lifestyle factors known to affect male fertility:

Obesity and Diet

There is strong scientific consensus that obesity is linked to lower male fertility. Fat tissue converts testosterone to estrogen and disrupts hormonal balance. Obese men tend to have lower testosterone levels and often lower sperm counts compared to lean men. A high Body Mass Index (BMI) correlates with reduced sperm concentration, poorer motility, and higher rates of abnormal morphology. One review noted that 15 of 23 recent studies found obesity significantly reduces sperm concentration. Obesity can cause a form of hypogonadism – essentially, the brain’s signals (LH, FSH hormones) that drive sperm and testosterone production get blunted. Additionally, obese men are more prone to erectile dysfunction and other problems that can affect fertility.

On the positive side, weight loss can improve sperm parameters and hormone levels. Studies show that when obese men lose weight (through diet or bariatric surgery), their testosterone often rises and semen quality can improve. This suggests the effect is at least partly reversible and directly tied to metabolic health. With global obesity rates skyrocketing over the same period that sperm counts allegedly fell, it’s very plausible that this is a major contributor. “We know that obesity is one of the strongest predictors of low testosterone, and to a lesser extent, of lower sperm counts,” says Dr. Jorge Chavarro. The mechanisms include hormonal disruption, increased scrotal heat (from body fat), and perhaps inflammatory or oxidative stress pathways that impair sperm.

Diet quality might also play a role. Some research indicates “Western” dietary patterns (high in saturated fats, processed foods) are associated with slightly worse semen quality, whereas diets rich in antioxidants, vitamins, and healthy fats (Mediterranean diets, etc.) are linked to better sperm health. Nutrient deficiencies (like vitamin D or zinc) can negatively affect fertility. That said, diet influences are moderate compared to factors like obesity and smoking.

Smoking, Alcohol, and Substance Use

Lifestyle habits strongly modulate reproductive health:

- Cigarette Smoking: Smoking is convincingly associated with lower sperm quality. Smokers have been found to have reduced sperm density, count, and motility on average. Toxicants in tobacco (like cadmium, nicotine, etc.) can cause oxidative stress on sperm production. Interestingly, smoking can transiently raise testosterone (nicotine triggers certain hormonal releases), but this doesn’t translate to better fertility – quite the opposite, as prolonged smoking damages the testes and DNA in sperm. Quitting smoking is generally recommended to men trying to conceive, as studies show better semen parameters and pregnancy rates in non-smokers.

- Alcohol: Heavy alcohol intake (chronic alcoholism) is known to suppress testosterone and can lead to testicular dysfunction (even testicular atrophy in severe cases). Moderate alcohol (a few drinks a week) doesn’t seem to have a large effect on sperm in most studies, but binge drinking or consistent heavy drinking is detrimental to male fertility.

- Marijuana and Other Drugs: Research on marijuana’s effect on sperm is mixed. Some studies surprisingly found marijuana users had higher sperm counts than non-users, hypothesizing perhaps a compensatory effect or some confounding factor. Other studies have found the opposite – that cannabis can lower sperm count and motility, possibly by disrupting the endocannabinoid system in the testes. The jury is still out, but heavy marijuana use is often discouraged when trying to conceive, just in case. Opiates (like heroin, or prescription opioids) definitely suppress gonadal function and can severely lower fertility during use. Anabolic steroid abuse (addressed below under testosterone therapy) is another major factor.

- Vaping: E-cigarette vaping is relatively new, so data is sparse, but initial animal studies and some human observations suggest nicotine and flavor chemicals in vapes could harm sperm quality. Since vaping often delivers nicotine (and other compounds) similar to smoking, it may carry similar risks for fertility. More research is needed, but caution is warranted.

- Heat and Occupational Exposures: Sperm production is temperature-sensitive (which is why testes are in the cooler scrotum outside the body). Frequent use of hot tubs or saunas, or professions like long-haul truck driving (sitting long periods with warm conditions) can impair sperm parameters. Even keeping a laptop directly on the lap for hours has been shown to raise scrotal temperature. These effects are usually reversible (sperm count rebounds after heat exposure is reduced), but they can contribute to fertility struggles for some individuals. Occupational exposure to radiation, heavy metals, or toxic chemicals can also reduce fertility – these are often case-specific (e.g. certain solvents affecting painters or pesticides affecting farm workers).

In summary, many lifestyle factors are within personal control and have a meaningful impact on an individual’s fertility potential. For the population as a whole, improvements in lifestyle (reducing obesity, smoking, etc.) could counteract some of the downward pressure on sperm counts.

Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs) – Plastics, Pesticides, and More

This is the factor that RFK Jr. and environmental health advocates emphasize the most. Endocrine disruptors are chemicals that can interfere with hormonal systems. They include certain industrial chemicals, pesticides (like organophosphate insecticides), plastic components like phthalates (used to make plastics flexible) and bisphenol-A (BPA), flame retardants, and others. These substances are ubiquitous in modern life – found in plastics, canned food linings, personal care products, household items, and pollution. There is legitimate concern that chronic low-level exposure to such chemicals could be affecting human health, including reproduction.

Shanna Swan’s research, for example, has linked pregnant women’s phthalate exposure to their male babies having a shorter anogenital distance (a marker some studies correlate with lower sperm count later in life). She and others suspect that fetal and early-life exposures to EDCs could be “programming” the male reproductive system in ways that result in lower sperm output in adulthood. It’s hard to prove this definitively in humans because you can’t ethically experiment on people’s exposures, but animal studies show certain chemicals can impair testicular development.

A 2023 systematic review and meta-analysis led by Dr. Melissa Perry addressed one piece of this puzzle: insecticides. They examined 25 studies over 25 years on men’s exposure to two widely used classes of insecticides (organophosphates and carbamates). The conclusion: there is consistent evidence of a strong association between insecticide exposure and lower sperm concentration in adult men globally. Men with higher levels of these pesticide metabolites in their bodies had significantly reduced sperm counts compared to those with less exposure. While correlation doesn’t prove causation, the consistency across studies and biological plausibility (these chemicals can mimic or block hormones) make it compelling. Dr. Perry stated, “The evidence has reached a point that we must take regulatory action to reduce insecticide exposure.”. In other words, this isn’t just theoretical – it’s enough human data to justify policy changes to protect public health.

Beyond pesticides, plastic-related chemicals are suspects. Phthalates, found in everything from vinyl flooring to food packaging to personal care products, can leach into our bodies. They are known to lower testosterone and have been linked to lower sperm quality in some studies. Bisphenol-A (BPA), used in hard plastics and can linings, is another estrogen-mimicking chemical with evidence of harming sperm in lab animals. Many countries have banned BPA in baby bottles, for instance, out of precaution.

RFK Jr. often speaks of a “toxic soup” of pollutants – mentioning things like atrazine (a herbicide), flame retardants, etc. There’s a lot of anecdote and some animal research behind these, but human epidemiological data is trickier. However, given that some chemicals (like certain pesticides) clearly correlate with sperm issues, it’s plausible that the cumulative mixture of various EDCs we’re exposed to could be contributing to a subtle population-wide decline in sperm and testosterone. It’s hard to quantify, but it’s an active area of research and concern. Importantly, any effects might be multigenerational: e.g., a pregnant woman’s exposure could affect her son’s sperm production decades later.

One challenge is that the human body is exposed to countless chemicals simultaneously. Pinpointing the effect of one or even a class of them is very hard. Moreover, lifestyle and chemical factors often go hand-in-hand (e.g., poorer communities might have more obesity and more pollutant exposure simultaneously). Still, many scientists agree with RFK Jr. on this point: we should reduce known harmful exposures where we can. As HHS Secretary, Kennedy’s push might involve stricter environmental regulations on certain chemicals, or promoting research into chemical effects on fertility. Those are reasonable policy discussions, even if the impetus is a bit exaggerated.

It’s worth noting the irony that RFK Jr. himself is on testosterone therapy (as he admitted in 2023, he takes prescription testosterone for “anti-aging”). The use of exogenous testosterone and anabolic steroids in men has become increasingly common, with many men in their 30s and 40s taking testosterone without clear medical need, seeking more energy or muscle. Unfortunately, external testosterone works as a male contraceptive. When a young man takes testosterone shots or gels, the body senses high hormone levels and shuts down the testicular production of testosterone and sperm via negative feedback. The result: the man often becomes azoospermic (zero sperm) within months. Around 75% of men on testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) develop azoospermia after 6 months of use, and many others have greatly lowered counts. Most of the time, the infertility from TRT is reversible if the man stops taking it – but it can take many months or even longer to recover, and some men never fully bounce back.

Kennedy, in advocating for male fertility, might want to highlight this lesser-known risk: the “Low T” treatment craze can paradoxically cause low sperm counts. Medical guidelines urge doctors to not give testosterone to men who still desire children, or if they do, to co-administer medications like HCG that maintain intratesticular testosterone to support sperm production. But many men obtain TRT from anti-aging clinics without proper counseling on fertility risks. The rise in recreational or non-essential TRT use among younger men could be another modern factor impacting some individuals’ fertility. (Kennedy is in his 70s and presumably not trying to have more kids, but it’s still an interesting contradiction: he warns of fertility problems while taking a drug that induces infertility. It highlights the complexity – boosting one aspect of “manhood” (vigour, muscle) can compromise another (sperm production).

In sum, the likely contributors to any sperm count decline are multifactorial: the Western lifestyle (poor diet, obesity, smoking) is a clear one, and environmental chemicals are a strong suspect as well. As Dr. Swan put it, “Chemicals in our environment and unhealthy lifestyle practices in our modern world are disrupting our hormonal balance, causing varying degrees of reproductive havoc.”. Her list includes “everywhere chemicals”like phthalates and BPA from plastics, certain cosmetics and pesticides, along with lifestyle factors (tobacco, marijuana, and obesity). While more research is needed to quantify each factor’s contribution, there’s enough evidence to justify efforts to mitigate these risks:

- Public health initiatives to reduce obesity and encourage healthier diets and exercise will likely benefit reproductive health (and health in general).

- Continued pressure to regulate and phase out harmful chemicals (for example, tighter controls on specific pesticides proven to impair fertility, or development of safer alternatives to phthalates in consumer products).

- Education for men about lifestyle choices (not smoking, moderate alcohol, avoiding excessive heat on testes, etc.) when planning to start a family.

- And yes, perhaps humorously, to caution young men that taking testosterone or even abusing anabolic steroids to look more “manly” can backfire when it comes to actual virility (sperm counts).

Reality Check: Not the End of the Human Species

As we near the conclusion, let’s address the apocalyptic tone of some warnings. Is humanity truly on a path to extinction via male infertility? Almost certainly not. Dr. Scott Lundy reassures, “This is not the end of our species as we know it.”. That may sound obvious, but it’s important to state given some headlines. Even in the worst-case scenario painted by Swan (median sperm count zero by 2045), that wouldn’t mean every man is infertile – median zero would mean half the men have some sperm and half have none, and presumably many could still reproduce with medical help. But again, that scenario is highly theoretical and extreme.

Human populations are still growing in many parts of the world (global population just crossed 8 billion). The fertility/birthrate declines in wealthy nations are more about choices and socioeconomic factors than biology. If at some point there were a true, widespread inability to conceive, society would undoubtedly respond with increased use of assisted reproductive technologies, and likely aggressive measures to identify and reverse the causes. We are far from that scenario.

However, this doesn’t mean we dismiss concerns about male reproductive health. Men’s reproductive health can be seen as a mirror of men’s overall health. Sperm count, testosterone levels, erectile function – these correlate with things like metabolic health, cardiovascular health, and mortality. For instance, a study in Human Reproduction found that men with infertility had higher rates of certain health problems later in life. Low testosterone in younger men can signal underlying conditions (diabetes, pituitary issues, etc.). So addressing the factors harming sperm counts (obesity, chemicals, smoking) is beneficial for far more than just fertility.

From a patient perspective, if you’re a man worried about your fertility: get a semen analysis if you have concerns or have been trying to conceive without success for 6-12 months. It’s a simple test that can provide reassurance or identify an issue. If an issue is found, many are treatable – for example, varicocele repair can improve sperm counts in a substantial subset of men. If no specific issue is identified, focus on general health: reach a healthy weight, eat a balanced diet, exercise regularly, don’t smoke or vape, go easy on alcohol, avoid illicit drugs, and be cautious with hot tubs and heat. Also, avoid unnecessary testosterone/supplements if you plan to have kids. These steps can optimize your natural fertility.

For medical professionals, the renewed spotlight on male fertility is an opportunity to emphasize a holistic approach: consider evaluating the male partner early in infertility workups (not doing so was an old bias), screen for modifiable factors, and counsel on healthy lifestyle for both partners. It’s also a reminder to stay informed on emerging research about environmental exposures – patients may ask about these, and while definitive advice is hard, we can at least inform them of potential risks (e.g., “There is evidence certain pesticides are linked with lower sperm counts; if possible, minimize exposure, wash fruits/veggies, consider organic if feasible, etc.”).

RFK Jr.’s reason for presenting this data may stem from a genuine concern that something in our environment or way of life is harming us – a viewpoint consistent with his activism. While his framing may be extreme, it has the effect of drawing attention to issues that have indeed been under-recognized. Historically, reproductive health (especially male reproductive health) has not gotten the attention it deserves in public health discourse. If nothing else, Kennedy’s outspokenness “opens the door” to talk about male reproductive trends, funding research on them, and implementing interventions. “Addressing a decline can have profound consequences for the multiple lifestyle and chemical risk factors implicated,” stated the 2021 Fertility & Sterility editorial. In that sense, raising an alarm – albeit with caveats – can spur beneficial action, as long as it’s guided by evidence and not panic.

Conclusion: A Balanced View

So, what’s the verdict? Yes, some studies show notable declines in men’s sperm counts and testosterone levels over the past several decades – and this is a legitimate public health concern worthy of further research and action. No, it does not mean we are facing imminent extinction or that today’s young men are half as fertile as their grandfathers in any practical sense. The reality is nuanced:

- RFK Jr.’s specific claim that a teenager has half the sperm count of a 60-something man is inaccurate – in fact, young men have higher sperm counts than older men (age causes a decline). The comparison should be across generations at the same age, not youth vs elderly.

- Data on generational changes in sperm counts are conflicting. A large body of evidence, including meta-analyses, indicates a downward trend of roughly 50% over ~50 years. However, many other studies find no decline, especially when looking at specific consistent cohorts. We must acknowledge scientific uncertainty here.

- Even if sperm counts have declined, the average man today is not infertile. Typical counts are still tens of millions per mL. Fertility in the population hasn’t collapsed; birth rates are down mostly due to later and fewer pregnancies by choice.

- The likely causes of any decline include modifiable factors (obesity, smoking, sedentary lifestyle, poor diet) and external factors (chronic exposure to certain chemicals). Tackling these – by promoting healthier lifestyles and reducing environmental toxin exposure – would improve public health regardless, and possibly improve or stabilize male reproductive health trends.

- Male fertility matters on an individual level (for couples trying to conceive) and as an indicator of men’s health. Infertility can be emotionally devastating for those affected, and male factors contribute significantly to it. Thus, more attention on diagnosing and treating male infertility is welcome. As Dr. Lundy emphasized, we should pay more attention to men’s reproductive health “not because of fears about humanity dying out, but to better understand men’s health”.

- For patients and the public: don’t panic due to scary headlines. Instead, use this information as motivation to live healthier and support policies that protect environmental health. If you have concerns about fertility, consult a medical professional – often there are solutions.

In concluding, RFK Jr.’s warnings contain a kernel of truth wrapped in a layer of hyperbole. The kernel of truth is that something does seem to be changing in men’s reproductive health metrics over time, and it’s worth finding out why. The hyperbole is implying we are on the brink of a dystopian fertility crash, which evidence does not substantiate.

A productive outcome of this discussion would be increased funding into reproductive epidemiology – including establishing surveillance of semen quality across populations, as some have suggested. Just as we track other health indices, tracking sperm health could help clarify trends and causes. It’s also a call to action for preventative health: what’s good for sperm (maintaining healthy weight, avoiding smoking, reducing chemical exposures) overlaps with what’s good for overall well-being and future generations.

In the end, ensuring the ability of our species to reproduce is undeniably important. But we should approach the topic with scientific rigor, not doomism. As with many health issues, awareness must be paired with accuracy. By examining the evidence objectively – as we’ve done here – we can address RFK Jr.’s concerns in a level-headed, evidence-based manner. There is no room for complacency about men’s health, but neither should we indulge in unfounded catastrophe narratives. The data will continue to evolve, and so will our understanding.

For now, the best course for patients and providers alike is: stay informed, encourage healthy lifestyles, minimize known reproductive risks, and support further research. The “sperm count debate” ultimately shines a light on how modern life might be affecting our bodies – a vital inquiry that goes beyond just reproduction and touches the core of public health and environmental responsibility.

References:

- Carlsen E, et al. BMJ. 1992 – Evidence for decreasing quality of semen during past 50 years (average sperm count fell from 113 million/ml in 1940 to 66 million/ml in 1990)

- Jørgensen N, Lamb DJ, et al. Fertil Steril. 2021 – Editorial: “Are worldwide sperm counts declining?” (notes Carlsen 1992’s conclusions “are patently false” due to subpar data; 8 studies found decline vs 21 found no change up to 2013)

- Olsen GW, et al. Fertil Steril. 1995 – Re-analysis of historical data (“Have sperm counts been reduced 50% in 50 years?” found only linear model showed decline; other models showed no consistent decline)

- Fisch H, et al. Fertil Steril. 1996 – Study of 1,283 U.S. men from 1970–1994 (no decline in sperm counts observed over 25 years; slight increase in mean concentration)

- Levine H, Swan SH, et al. Hum Reprod Update. 2017 – Systematic review/meta-regression (1973–2011) reporting ~52% decline in sperm concentration and ~59% decline in total count among Western men

- Swan SH. Count Down. 2021 – Book highlighting falling sperm counts “imperiling the future of the human race,” projecting median sperm count could reach zero by 2045 (Guardian coverage)

- Levine H, Jørgensen N, Swan SH, et al. Hum Reprod Update. 2023 – Updated meta-analysis (1973–2018) showing 51.6% global decline in sperm concentration; decline observed in South/Central America, Asia, and Africa as well

- Lundy SD, et al. Reprod Biomed Online. 2022 – Analysis of U.S. sperm counts (subtle decline 1970–2018 that likely wouldn’t affect fertility; “no cause for widespread panic”)

- Chavarro JE – Quoted in NBC News (2025) on obesity’s impact (obesity strongly predicts lower testosterone and somewhat lower sperm count; obesity impairs brain reproductive hormones)

- Perry MJ, et al. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2023 – Systematic review & meta-analysis: organophosphate and carbamate insecticide exposure is strongly associated with lower sperm concentration in men

- Swan SH – Interview/quotes (NBC News 2025) standing by her team’s results and linking chemical exposures to reproductive declines

- Pacey AA. Asian J Androl. 2013 – Commentary: “Are sperm counts declining or did we change our spectacles?” (cautions differences in lab methods can mislead trends)

- Jørgensen N, et al. BMJ Open. 2012 – Study of 4,867 Danish men (1996–2010) found increase in median sperm concentration from 43 to 48 million/mL and total count from 132 to 151 million

- Travison TG, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007 – Population-level decline in testosterone in American men (~1% per year drop independent of aging; a 65-year-old in 2002 had T 15% lower than a 65-year-old in 1987)

- Reuters Health. 2007 – Report on Travison study (“Men’s testosterone levels declined in last 20 years”; trend unexplained by weight or smoking alone, likely environmental)

- Darand M, et al. Reprod Health. 2023 – Review of obesity and sperm (overweight/obese men have lower sperm counts; high BMI negatively affects sperm count, motility, morphology, and testosterone)

- Fantus RJ, Halpern J, et al. Int J Impot Res. 2023 – “Broad reach and inaccuracy of men’s health info on social media” (found semen retention had 1.2 billion TikTok impressions and was top topic; highlights popularity of this narrative)

- Genesis Fertility (Blog). 2022 – “The Slippery Slope of TRT” (75% of men on testosterone therapy develop azoospermia within 6 months; TRT suppresses pituitary signals needed for sperm, sometimes with incomplete recovery)

- Honig SC – Quoted in NBC News (2025) on varicocele (present in ~35% of men with fertility problems; a leading treatable cause of male infertility)

- Bendix A. (NBC News, July 3, 2025) – “RFK Jr.’s warnings about sperm counts fuel doomsday claims…” (article summarizing RFK Jr.’s claims and expert rebuttals: young men have higher sperm counts than older; data on teens is scarce; no full-blown fertility crisis)